Shijô

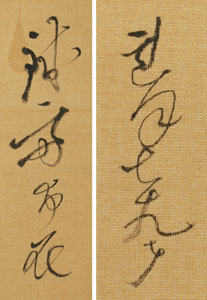

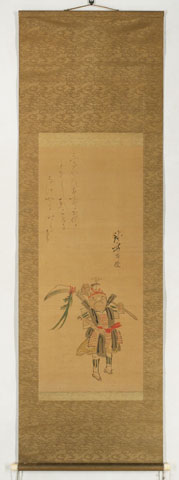

The fifth day of the fifth month, waiting for the cuckoo, Benkei dollSigned: Tessai ga .., Rengetsu nanajûku (79) sai

Seals:

Technique: colours on silk 76 x 32,4

Date: 1869

Mounting: bronze damask 142,5 x45

Condition: lightly toned, a small stain and a restoration near the bottom roller, otherwise very good condition

The waka reads:

ふきわたすあやめにおのがときしらば軒ごとになけやま時鳥。

”Fukiwatasu ayame ni nodoka toki shiraba nokigoto ni nake yamahototogisu.

“Would they know,

Now that the breeze so gently

Smooth the irisses

On every eave they are singing

The mountain cuckoos”

On the fifth day of the fifth month, according to the old calendar, people celebrated Ayama no sekku and Tango no sekku, both the iris and the boys’ festival. The combination of Benkei and a waka about irises is therefore not as strange as it seems.

Tessai was born in Kyoto into a family selling robes and accessories for the Buddhist clergy. As a result of a childhood illness he became partly deaf. It was therefore considered improbable that he would ever become a successful shopkeeper. Instead he went to study the Japanese classics in order to become a Shinto priest. He also did Chinese studies, specializing in the teachings of the neo-confucianist Wang Yang-Ming. Later he would study Buddhism, literature and Shingaku, a semi-religious system for self-cultivation.

As a youth Tessai met Rengetsu and became her special protégé. She taught him waka and encouraged his artistic inclinations. Tessai was mainly self-taught, indepently studying Nanga painting and learning from friends. He was, however, strongly influenced by Shinten’ô (# 34).

In the final years of the Tokugawa era Tessai was involved in the pro-imperialist movement. For fear of being arrested he left Kyoto in 1861 and travelled to Nagasaki. It was the first of many trips; Tessai became and avid traveller. In 1882 he settled in Kyoto where he spent the rest of his life. Although he worked as a priest at several Shinto shrines, he saw painting as his chief occupation. Between 1894 and 1904 he was a teacher at the Kyoto Prefectural Art School and he was a regular contributor to exhibitions of the Nanga Society. In 1917 he was appointed Artist to the Imperial Household and towards the end of his life he received an honorary court-rank. Tessai is often seen as the last great exponent of the Nanga school.

Reference:

Kanazawa

Kato 1998

Roberts p. 181

Araki pp. 2754-2755

Aburai pp. 266-267

Morioka & Berry ‘99 pp. 116-121

Morioka & Berry ‘08 p. 305-06

Rengetsu is one of those extraordinary figures in Japanese art history, one of a kind.

Rengetsu was born in Kyoto. Within a few days after her birth the Õtagaki family adopted her. In 1798 she moved to Kameoka castle to serve the Matsudaira family. Here she studied the woman’s pursuits such as poetry and calligraphy, but she received training in martial arts as well. In 1807 she returned to her family in Kyoto where she married her adopted brother, a young samurai called Mochihisa. In the eight years of her marriage she gave birth to three children, who all died shortly after their birth. In 1815 she divorced her husband, who was to die shortly after. She remarried but already in 1823 her second husband died. She cut her hair and became a nun and took the name Rengetsu, Lotus moon.

With her daughter from her second marriage and her stepfather she moved into a small building on the grounds of the Chion-in. Two years later her daughter died. Without means of support she moved to Okazaki in the Kyoto area together with many artists, where she produced pottery and studied Shijô painting with Matsumura Keibun (1779-1843). She fell in love with Keibun and they lived together. She intensively studied waka. In spite of being a nun, men made advances to her, but not being interested, she pulled out her teeth to look less attractive and to strengthen her inner self. Her pottery became such a big success that she escaped her customers many times and moved more than thirty times, even thirteen times in one year.

She became close friends with Tessai and even tried to adopt him as a son. For the last 25 years of her life he helped and accompanied her. On the invitation of the Abbot Wada Gozan (Gesshin) (1800-1870) she spent her last years in a tea hut on the grounds of the Shinko-in temple where she deeply immersed herself in the study of Buddhism but she also continued her artistic occupations.

Reference:

Canberra 2007

Roberts p. 129

Fister '88 pp. 144-159 (# 69-76)

Price: SOLD